World’s largest climate action march: Episcopalians protest for changePosted Sep 23, 2014 |

|

Don Robinson, a member of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Northampton, Massachusetts, and a trustee of the Diocese of Western Massachusetts, lifts his hands during a moment of silence at the People’s Climate March Sept. 21, in New York, two days before the United Nations’ Climate Summit commenced. Photo: Amy Sowder

[Episcopal News Service] Don Robinson’s right hand gripped a leaf of curly kale, pointing it toward the sky as he lifted his eyes in silent prayer.

Robinson, from the Diocese of Western Massachusetts, stood among more than 200 Episcopalians and Anglicans from as far as Alabama, Oregon and South Africa, all squeezing into their designated patch of 58th Street in Midtown, Manhattan.

He stood for the human right to save Earth and all of its living things from the snowballing effects of climate change. “We have a responsibility as stewards of God’s creation,” Robinson said.

On Sunday, Sept. 21, more than 310,000 people of all faiths and none joined the People’s Climate March, the largest demonstration for climate action in history, while a series of religious events included a multifaith evening service at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York.

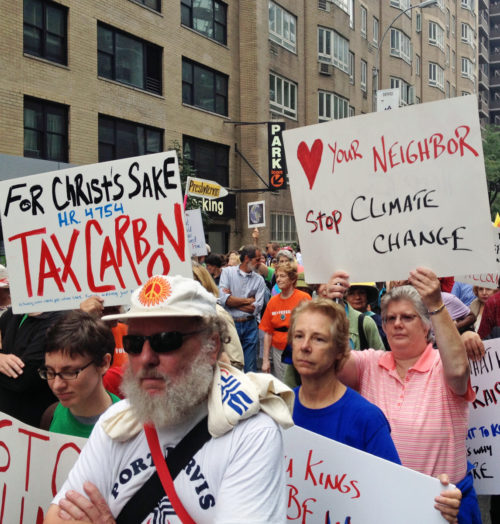

Episcopalians from across the nation and a few other countries joined the interfaith-themed section of the People’s Climate March in New York Sept. 21, holding protest signs, carrying banners, singing, praying and chanting. Photo: Amy Sowder

The 2.2-mile march snaked from 93rd Street and Central Park West to Columbus Circle down through Times Square to 34th Street. Near the back, the Episcopal contingent held signs such as “There is no Planet B,” “For Christ’s Sake, Tax Carbon” and “I’m marching for wildlife (That means humans too).”

The march was endorsed by more than 1,200 organizations, including the nation’s largest environmental organizations, labor unions, faith-based and social justice groups.

It’s a movement spurring action much wider than New York, or even the U.S. More than 2,800 solidarity events unfolded in 166 countries, with demonstrations spanning from Sydney, Australia and Budapest, Hungary to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The global initiative was planned two days before the United Nations Climate Summit, convened by Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, kicked off Sept. 23 at the U.N. headquarters in Manhattan. The summit delayed the opening of the general debate by one day, to Wednesday, during the 69th session of the U.N. General Assembly, which extends from Sept. 16 to Oct. 1. Ban, who also participated in the march, invited leaders from government, finance, business and civil society to galvanize at the summit and bring bold action-oriented announcements that will reduce emissions, strengthen climate resilience and mobilize political will for a meaningful legal agreement in Paris in 2015.

Besides Ban, some of the most well-known march participants were former Vice President Al Gore, musical legend Sting, and actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo.

Meanwhile, the leaders of the Episcopal and Lutheran churches together issued a pastoral message on climate change Sept. 19.

Climate change is “going to affect the poorest among us first,” said Brother Bernard Delcourt from The Order of the Holy Cross, an Anglican Benedictine monastery in West Park, New York. “People who depend on natural resources for their livelihoods in developing countries are already being hit.”

Lella Lowe, a member of the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer in Mobile, Alabama, scheduled her vacation to attend the march. She helped form the Mobile Environmental Justice Action Coalition to prevent Mobile from turning into a major transportation hub for tar sands oil.

“You either have a movement with money or a movement with people, and when you don’t have the money, you have to motivate the people,” Lowe said. “It’s time to see our world as interconnected and that everything we do affects others. It’s critical, and there’s a lot of denial.”

Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner was set to share her story at the U.N. Climate Summit’s opening ceremony on Sept. 23. Two days earlier, the young mother from the Marshall Islands stood onstage among several activists at a pre-march press conference to tell the crowd how her home is in danger of disappearing due to rising seas caused by global warming. Her island is two feet above sea level.

“We need to act now. We cannot wait. We only have one land to call home. We need you,” Jetnil-Kijiner said.

The People’s Climate March in New York led by indigenous and frontline communities from across the globe to highlight the disproportionate impact of climate change – from communities hit hardest by Hurricane Sandy to those living near coal-fired power plants and oil refineries to people living in island nations already faced with evacuating their homes. Photo: Amy Sowder

During the march, people and groups with political, religious and other differences united around a common theme. Interfaith groups joined with scientists for “The Debate is Over” section. Other crowds included labor unions; environmental justice; renewable energy; food and water justice; anti-corporate campaigns; and indigenous communities.

In the interfaith section, Episcopalians marched with Jews, Baptists, Mennonites, agnostics, Quakers, ethical humanists, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Hare Krishnas.

An inflatable mosque floated near a wooden replica of Noah’s Ark. Earth balloons bobbed over the sea of people.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration meteorologists announced last week that this summer was the hottest on record globally.

“Despite the U.N.’s efforts, member states have not done what needs to be done – not even close – and carbon levels are increasing, not decreasing. It’s not only more worrisome than ever, it’s morally wrong,” said the Rev. Canon Jeff Golliher of St. John’s Church in Ellenville, New York, and chairman of the executive group of the Episcopal Diocese of New York’s Committee on the Environment.

Most of the problem, he said, is created by the energy policies in the world’s three biggest economies with large population growth: the U.S., China and India.

Those countries need to figure out how to create more clean energy rather than burning fossil fuels, Golliher said, because creating energy requires a lot of water, “and we’re seeing water shortages.”

“We may be creating solutions that benefit the wealthy more than the poor,” said Golliher, who attended the Stockholm International Water Institute’s annual conference Aug. 31 to Sept. 5. “The moral issue is not whether climate change is real – most of the population knows this by now. It’s what kind of debate we’re having to create an economy based on human rights and sustainability for everyone to thrive.”

The U.S. National Academy of Sciences released research in 2013 showing abrupt climate changes are already underway, while other potential threats are not as imminent. Warmer Arctic temperatures have caused a rapid decline in sea ice in the last decade. Rising sea levels threaten coastal regions and islands.

Academy scientists report that another abrupt change is underway: increased extinction pressure on plant and animal species due to the current pace of climate change, a warming event expected to increase over the next 30 to 80 years. The number of frost-free days, length and timing of growing seasons and the frequency and intensity of extreme events are examples of changes happening so rapidly that some species can neither move nor adapt fast enough. Combined with other sources of habitat loss, degradation and over-exploitation, the problem is even worse, according to the report.

Then there are the increasing periods of drought in western U.S., northern Iran and Africa. “The thing scientists are worried about most is the unpredictability. Because that’s unmanageable,” Golliher said.

“The carbon is just one issue. It’s the indicator. It has to do with power, equality and justice. What kind of world do we want to live in?” Golliher asked.

While initial estimates of the People’s Climate March in New York at 2 p.m. on Sunday, Sept. 21, calculated the crowd to be about 310,000, by 5 p.m. so many others streamed in that the final participation count neared 400,000 people. Photo: Amy Sowder

While legions swarmed the streets of Manhattan to send a message to members of the U.N., 30 faith leaders representing nine religious traditions signed their names to a statement calling for concrete actions to curb carbon emissions. The interfaith conference was co-hosted by the World Council of Churches, which includes 345 churches representing about 560 million Christians worldwide, and Religions for Peace, an interfaith coalition with members in more than 70 countries. Signatories hailed from 21 countries on six continents.

The march was particularly focused on highlighting the intersection between people’s needs and climate change, including housing, employment and education, said Elizabeth Yeampierre, executive director of Uprose, which helped lead the community response to Hurricane Sandy after it hit New York in October 2012.

“I think there is a fear of working with people from different communities,” Yeampierre said.

“Regardless of what your field is, your passion, everyone is affected by climate change,” she added, acknowledging that the disenfranchised and the country’s top 1 percent are taking action, and doing it publicly.

Significant and far-reaching change all comes down to money and fossil fuel corporations make a lot of it, said Stanley Sturgill, a retired underground coal miner from Kentucky,

“But if we don’t do something, we won’t be able to breathe or have water. We’re fighting over gas and oil, but soon we’ll be fighting over water. Once you lose water, that’s it.”

The Rockefeller family, heirs to the Standard Oil Co. fortune, will divest their foundation’s fossil fuel investments and put them into renewable energy sources, according to an announcement timed in conjunction with the People’s Climate March and the U.N. Climate Summit.

Robinson, as he marched with his fellow Episcopalians and interfaith activists, said the Diocese of Western Massachusetts decided in early September to shift about 20 percent of its $60 million of investments from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

“We took a vote after a long, hard debate. It reflects the bishop’s commitment,” Robinson said.

He traveled to the march on the “Episcopalians on a Journey of Hope” bus filled with more than 55 people from the Episcopal Church’s Province 1 dioceses of New England. Organized by the Rev. Stephanie Johnson, the province’s environmental stewardship minister, the bus picked up students from Berkeley Divinity School at Yale.

“I think this march can make a difference,” Johnson said. “I’ve been working in the environment field for over 30 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this.”

Marching near Robinson and Johnson, Anne Rowthorn, member of St. Ann’s Episcopal Church in Old Lyme, Connecticut, nodded in agreement.

“The No. 1 pro-life issue is the life of our planet,” Rowthorn said. “It’s the No. 1 issue of our time.

“We need to put our feet to the pavement to let our leaders know they have disappointed us. This is a message to those leaders meeting this week.”

Social Menu