Church in Navajoland confronts ministry challengesPosted Jan 23, 2013 |

|

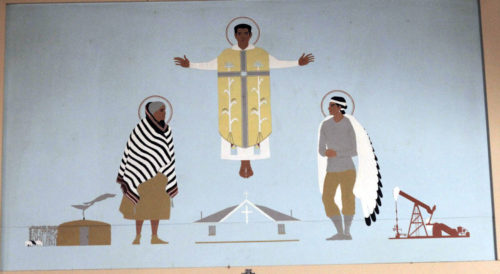

A Navajo rendition of the ascension hangs above the altar at St. Michael’s Church in Upper Fruitland, New Mexico. In addition to Mary, Jesus and St. Michael, it includes a hogan, or traditional Navajo dwelling, the church and and oil derrick. ENS Photo/Lynette Wilson

[Episcopal News Service] Every third Sunday, Deacon Paula Henson travels 200 miles round trip from Fort Defiance, Arizona, to St. Joseph’s House Church in Many Farms, where she slowly is building a congregation that last November received four new baptized members.

An Anglo priest established the house church some 50 years ago, but, more recently, firmly planting a church in Many Farms has taken on a greater sense of urgency for Henson because the matriarch of the local family has been ill.

“It’s time to step it up and be there for her daughters and the little ones” so they can carry on a church there, she said. The plan, she added, is to clear out the matriarch’s hogan, or traditional Navajo dwelling, and create a sacred worship space.

It’s a fitting gesture in a matriarchal society, where family connection means everything, people introduce themselves by clan name, and Episcopalians can trace their church affiliation back, in some cases, to great-great-grandmothers.

“The bulk of the church is family and extended family,” said Navajoland Bishop David Bailey in a November interview with ENS in New Mexico.

In the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, between 4,500 and 5,000 Navajo would have identified themselves as Episcopalians. Today, Navajo Episcopalians number between 900 and 1,200.

In 1978, the Episcopal Church carved out parts of the dioceses of Rio Grande, Arizona and Utah within and surrounding the 27,000-square-mile Navajo reservation in an area the size of West Virginia to create the Navajoland Area Mission. It was an effort toward unification of language, culture and families.

Unfortunately, when the Episcopal Church designated the mission, it didn’t provide the necessary resources to build it up, said Bailey in a July letter to church leaders.

“Changing times and several internal challenges have contributed to an inability of the larger church to meet the needs or enable the success of the mission,” he wrote. “No substantive efforts were undertaken reflective of a long-term commitment to create, implement and build a sound foundation for the future of the church in Navajoland.”

That’s all changing. Since Bailey became bishop in 2010, the area mission has invested $190,000 in buildings and maintenance costs because, as with many small dioceses that have deferred maintenance costs, they didn’t have places to gather and worship. He also has identified and empowered Navajo clergy and laity. See related story.

‘Living off borrowed money’

At 72, Bailey is “retired” and was appointed by Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori to serve as the bishop in Navajoland. His focus, he said, is more administrative than pastoral.

“I’m building the foundation,” he said. “I am cognizant of my age, and whoever does follow me will have something to build up.”

The Episcopal Church’s 2013-15 budget approved by approved by General Convention in July 2012 designated $333,333 annually for Navajoland, leaving the church almost $300,000 short of its $600,000 annual budget.

“We are living off borrowed money,” said Bailey. “We are scrambling to raise dollars.”

To bridge the budget gap, he said, Navajoland is implementing new programs, addressing building-maintenance concerns, providing training for clergy and laity and developing new revenue opportunities.

The church owns 150 acres of land in the church’s three regions covering New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, that can be developed, said Bailey.

At Fort Defiance in Arizona, where the church already manages rental properties, the plan is to build an recreational vehicle park. At St. Mary in the Moonlight, located near the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park in Utah, a highly popular tourist destination, the goal is to build a retreat center. In addition to a hostel at St. Christopher’s Mission, also in Utah, an agriculture/aquaculture project is in development. And in Farmington, New Mexico, where the church has its administrative offices, it would like to build low-income housing for single mothers on 40 acres of what once was a sand and gravel pit.

“We’re not going to generate $600,000, but maybe $200,000,” said Bailey.

Building partnerships

Building up supportive partnerships across the Episcopal Church also is essential to Navajoland’s development. Bailey said he believed that, if the people knew more about the church in Navajoland, they’d want be part of it.

“We’re not looking for a handout, we’re looking for a hand up. I know that’s a worn-out statement, but that’s what we are looking for,” he said. “It used to be that people would come out and do their thing. Let’s be clear about what we need and what we want to partner with you to do.”

One milestone for Navajoland is a renewed companion relationship with the Diocese of the Rio Grande and its recently elected Bishop Michael Vono.

“This is significant because we were out of relationship for 25 years,” said Bailey. “The two previous bishops of Rio Grande wanted nothing to do with indigenous beliefs.”

Not all partners have been church partners. For instance, Good Shepherd Mission in Fort Defiance partnered with Texas A&M University’s veterinary school to spay and neuter dogs and cats. And in Bluff, St. Christopher’s Mission partnered with Venture Utah, a nonprofit coalition focused on youth, to run a summer horse-therapy clinic. The mission also is partnering with Utah State University to set up an extension-learning center, which will include video-conferencing capabilities.

Even with the center in its early development, the community is looking at it as an anchor for many other youth and family services in vocational and academic training, and perhaps to boost St. Christopher’s agricultural project, which consists of six acres devoted to community farming, said the Rev. Red Stevens, who serves St. Christopher’s and is the ministry developer and missioner for the Utah region.

“We’re looking forward to seeing that as a focus for our continuing services to our own community and our wider client-service area, which reaches roughly from St. Christopher 25 miles north and south and 10 miles east and west,” Stevens said. “We have a large area of sparsely populated homes and family compounds, and this will provide a place where people can get educational resources, recreational resources and family-strengthening resources.”

St. Christopher’s Mission in Bluff, Utah, is the oldest, continuous mainstream Christian outpost in operating in the heart of Mormon country. ENS Photo/Lynette Wilson

St. Christopher’s Mission is the oldest, continuous mainstream Christian outpost in Bluff, in the heart of Mormon country; the next nearest Christian mission is in Round Rock, some 60 miles away. St. Christopher’s serves between 350 and 400 clients, providing water, food and clothing.

St. Christopher’s owes some of its successes to Episcopal Church partnerships, including All Saints in Beverly Hills, California, Annunciation in Lewisville, Texas, St. John’s in Kingston, New York, and others.

“We’d still exist, but they provide a richness that we need, moral and financial support, and it goes way beyond us,” Stevens said. “When they do vacation Bible school, kids come from all over.”

Being in community

The Navajoland Area Mission has three major congregations in New Mexico and Utah and two major congregations and two house churches in Arizona, where most of the Navajo reservation is located. By offering programs and services for dealing with inter-generational trauma – the long-lasting effects of suffering, violence and abuse, particularly in reference to the historical sufferings of indigenous people, which can lead to violence and substance abuse – the church hopes to raise its profile and attract new members.

The area’s social challenges “take on their own spiritual characteristic because people are so interconnected; it becomes everyone’s problem,” said Stevens.

Deacon Cornelia Eaton and her mother, Alice Mason, a longtime lay minister who served St. Michael’s in Upper Fruitland, New Mexico. Many of the Episcopalians in Navajoland can trace their church membership back generations. ENS Photo/Lynette Wilson

Cornelia Eaton, a postulant and Bailey’s assistant in Farmington, agreed. While each ministry is unique, all struggle with the same challenges of poverty, substance abuse and domestic violence, she said.

Between 125,000 and 150,000 Navajo live on the reservation. Many work in extractive industries, such as oil, uranium and petroleum, but it’s estimated that half of the population is unemployed and 50 percent lives in extreme poverty. Most parishioners either don’t have vehicles or are too old to drive.

Asked what they need, the first response clergy and lay ministers give is “reliable vehicles” and the second is gasoline. “The main problem is isolation and gas prices,” said Stevens. “It is 30 miles round trip to church. Everything is so far away from anything else. We travel so much.”

It was her travels past St. John the Baptizer in Montezuma Creek, Utah, that brought lay pastor, Lily Henderson, there.

“I used to drive up and down this road and the church was shut down, and I prayed about it and I left my job,” said Henderson, who worked for years in early-childhood development before taking over at St. John the Baptizer.

Henderson faces many challenges. She hauls water from St. Christopher’s Mission, some 12 miles up the road, because the water on the St. John’s property is contaminated. The floors are curling in the sacristy. And the old parish hall must be demolished because it’s unsafe for children.

Like others, she said one of her biggest concerns is transportation and high gas prices. The children she serves mostly have difficult home lives, coming from alcoholic, single-parent, low-income families. She does, however, have a van to use to get supplies and to pick up children for Sunday school, she said.

“They really enjoy coming over to have something to eat. This is a safe place to be, to have someone to be with, to talk to them, to know that we care about them,” said Henderson.

LaCinda Hardy-Constant, a postulant and community organizer serving Good Shepherd Mission in Fort Defiance, leads a partnership between the congregation and the community that began about a year ago.

“We started to identify needs and assets that exist in the community,” she told ENS. “One of the main issues is gang violence and youth.”

Five gangs have become a “constant menace” to the community, and talks with the community revealed that the elderly population lives in fear, said Hardy-Constant, who also serves on the Executive Council Committee on Indigenous Ministry. “Once the sun goes down, they are not going outside.”

In response, Good Shepherd instituted a neighborhood watch program and is working to provide volunteer opportunities for young people.

Elders often express concern that the children are not getting enough spiritual direction, Hardy-Constant said. Without that, they ask, how will they follow their journey?

“The church is for the kids to give them a direction as they grow up,” she said. “That inspiration is what at child will keep forever.”

This is something Hardy-Constant and others who’ve grown up in the Episcopal Church in Navajoland know. Like many other children, she was “born and raised” at Good Shepherd.

“We talk about Good Shepherd and how it was the heart of Navajoland,” she said. “When you are raised in the church, you see different levels of strength and weakness. We’ve come a long way in Navajoland. We are slow like a turtle.”

It was the Rev. Davis Givens, an Anglo priest, who some 50 years ago started driving his Model T the long distance from Fort Defiance out to the house church in Many Farms, who founded the ministry, which Henson has chosen to rebuild.

“It means a lot [to the family] that Paula still goes out there,” said Hardy, who told the story of Givens driving his Model T across Navajoland.

Deacon Catherine Plummer also drives long distances to serve her parish. She lives in Bluff and serves part time at St. Mary of the Moonlight in Oljato, an hour’s drive southwest. The arrangement can be difficult for her and the people she serves.

She typically drives out on Friday to give her members the Sunday lessons, so they can come prepared; she visits shut-ins, offering morning prayer and consecrated bread and wine. On Saturdays she tries to catch the people she missed on Friday.

Plummer is a fourth-generation Episcopalian. Her great-great-grandmother on her mother’s side was an Episcopalian, and she is the widow of Bishop Steven Plummer. She is looking forward to being ordained a priest and moving out to Oljato. It’s important, she said, that the parishes have ordained leaders.

“They don’t feel like they have anybody out there,” she said.

— Lynette Wilson is an editor/reporter for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu