Can bad religious art be good?Posted Nov 15, 2012 |

|

[Episcopal News Service] On a recent visit to a museum dedicated to Christian religious arts, I came up with a potential addition to the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not use life-size wax mannequins wearing bad wigs and bed sheets to illustrate scenes from the life of Jesus.

[Episcopal News Service] On a recent visit to a museum dedicated to Christian religious arts, I came up with a potential addition to the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not use life-size wax mannequins wearing bad wigs and bed sheets to illustrate scenes from the life of Jesus.

I feel a bit bad being cynical about this museum, which was founded with the best of intentions and which I’m sure is meaningful to many who visit it. But as I viewed its Precious Moments figurines, paint-by-number Last Suppers, and Technicolor depictions of angels borne on puffy clouds, I found myself getting increasingly grumpy.

The museum illustrates one of the ironies in Christianity. Some of the world’s most sublime works of art were created out of profound religious devotion—think of Raphael’s Madonnas, Michelangelo’s David, and Orthodox icons gleaming with gold. At the same time, a lot of Christian art is sentimental, cheesy and even a bit creepy. If you doubt me, search for “bad religious art” on the Internet and be prepared for a torrent of rainbow-festooned Biblical scenes, angels borne on shafts of light, and Jesus carrying people across beaches.

The museum gave me some sympathy for Muslim and Jewish traditions, which have strict guidelines regarding religious art. We Christians have struggled at times with this issue as well, most spectacularly in the eighth century when zealots smashed Byzantine icons because they were believed to violate the Biblical prohibition against graven images. We eventually made our peace with religious art, though some of us are more comfortable with it than others. Think of the contrast between a Roman Catholic church filled with ornate statues and paintings and the austerity of a Quaker meeting house.

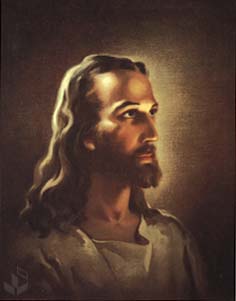

What’s sentimental to one person can be profoundly meaningful to another, of course. Though the majority of the art in the museum didn’t appeal to me, one image made me stop and linger for a long time: a picture of Jesus that I remember hung on the walls of the Sunday School rooms in my childhood church. The image is out-of-fashion now, for it shows a Northern European-looking savior with a bit of a movie-star vibe about him. But something about that image moved me. It was my first picture of Jesus, and my visceral reaction to seeing it again proved that it’s still deeply lodged in my psyche.

The museum’s many mass-produced images gave me a renewed appreciation for the power of true folk art, which often deals with religious themes. In my home church, for example, we have a colorful tapestry created by poor women in rural Mexico. Each of its embroidered panels depicts a story of some miraculous event, from recovery from a serious illness to the rescue of a child from a well. While the figures are crudely drawn and the embroidery simple, the images radiate devotion and thanksgiving.

Commercial images, as opposed to fine art or folk art, are designed to appeal to the widest possible audience. By taking the safe route, they rarely challenge, puzzle, or inform us. Great art, in contrast, pulls us ever deeper. I love the story of how the author Henri Nouwen became fascinated by Rembrandt’s painting of the return of the Prodigal Son. Nouwen traveled to St. Petersburg to spend several days sitting in front of the painting, contemplating its nuances and absorbing its beauty. Rembrandt’s image made him probe deeply into the layers of meaning in the parable, helped him realize how he had played all the roles in the story in his own life, and eventually led him to write the book The Return of the Prodigal Son. I don’t think that sort of transformative experience can happen with a Thomas Kinkade image, as cozy as his little churches filled with light may be.

At the same time, a lot of people like pictures of idyllic churches nestled in snowy valleys and adorable little angels with rosy cheeks. As I left the museum, I somewhat reluctantly concluded that Christianity did the right thing in telling those eighth-century iconoclasts to take a hike. We need to say yes to it all—the velvet paintings as well as the great masters, the Precious Moments figurines as well as contemporary artists who stretch our definition of what religious art can be. The Holy Spirit isn’t an artistic snob, and we shouldn’t be one either.

– Lori Erickson writes about inner and outer journeys at www.spiritualtravels.info. She serves as a deacon at Trinity Episcopal Church in Iowa City, Iowa.

Statements and opinions expressed in the articles and communications herein, are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of Episcopal News Service or the Episcopal Church.

Social Menu