WEST TEXAS: Fighting wildfiresPosted Jul 2, 2012 |

|

Nature Conservancy firefighters watch as smoke billows from wildfire in basin below. Photo courtesy of Dan Snodgrass

[Diocese of West Texas] It began when a clap of dry lightning exploded on the parched “sky island” high in the Davis Mountains of West Texas. With no rain to douse the sparks, the wind-fanned smoldering embers quickly grew into a runaway wildfire, feeding on the tinderbox of dried grasses, piñon pines and juniper.

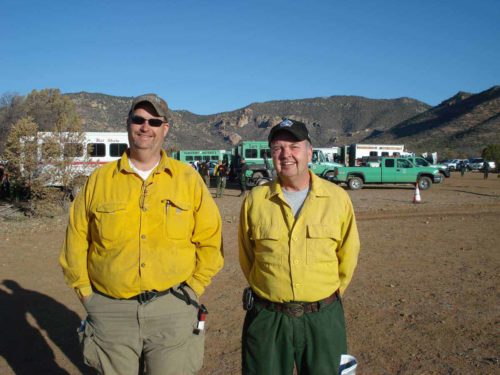

Volunteer firefighters from the Fort Davis area battled the blaze before calling for reinforcements from the Texas Forest Service. Among the hundreds of responders were two from St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church in Blanco , a vibrant mission in the heart of the Texas Hill Country.

Neither knew the other was there, much less that they were both wildland firefighters.

As associate director of land conservation for The Nature Conservancy, Dan Snodgrass oversees all 37 Nature Conservancy properties in Texas. When that bolt of lightning struck on April 24, 2012, he took a special interest in it. The fire was on the Davis Mountains Preserve — one of his preserves.

The Davis Mountains Preserve is among the most unique and majestic areas of Texas. With elevations from 5,000 feet to the 8,378-foot summit of Mount Livermore, the preserve is an isolated “sky island” of diverse plant and animal life surrounded by the expansive Chihuahuan Desert.

Since 1997, The Nature Conservancy has managed to cobble together a 32,000 acre tract carved out of the U Up U Down Ranch and other properties. Another 70,000 acres are protected in conservation easements adjacent to the preserve.

Snodgrass, like many Nature Conservancy employees, has undergone the same rigorous wildland fire fighting training and certification that professional firefighters undertake. “We slip right in with them,” he said.

So when he received word that the fire was burning his preserve, he grabbed his Nomax protective clothing, hardhat and headed to the fire from his home in Johnson City, Texas.

As Snodgrass rushed to the fire, a call went out to Hunter Wistrand, a retired U.S. Forest Service ranger and firefighter now in his second year as bishop’s warden at St. Michael. The Texas Forest Service calls Wistrand when a fire gets big enough to require extensive mobilization.

A wildland fire fighting operation is akin to a military campaign, complete with strict rules of engagement and a top to bottom command structure. At the top of the Davis Mountains command structure was Paul Hanneman, who himself has a link to St. Michael. His mother-in-law is Janet Smith, a long-time member of St. Michael.

Wistrand was assigned the job of operations section chief, which gave him the responsibility of making day-to-day fire fighting assignments. Based on his recommendations, the fire fighting resources were doubled.

Aircraft ranging from large tankers to single-engine planes and helicopters were brought in to drop water and retardants on the fire. Hot shots – those 20-person crews that cut fire lines by hand – arrived from as far away as Virginia and started scratching out a six-mile fire break to keep the blaze from spreading. A professional caterer was even called in to feed hundreds of empty stomachs.

On this fire, Snodgrass and other Nature Conservancy employees supported the operation by providing water, housing and strategic advice about how to fight the fire on preserve property.

The biggest threat was to the isolated Davis Mountains Resort, an eclectic subdivision of 250 permanent residents and 400 absentee landowners adjacent to the Nature Conservancy and downwind from the fire.

One morning, as Snodgrass reviewed the action plan for that day’s fire fighting, he noticed Wistrand’s name. “I saw his name there and thought, ‘I know that name,’ but couldn’t place it. Then at the morning briefing I saw Hunter,” Snodgrass said.

“I looked out in the crowd and saw Dan,” Wistrand said. “I shook his hand and asked him what he was doing there.”

Snodgrass asked Wistrand what he was doing there.

“He didn’t know I worked for the Texas Forest Service and I didn’t know he worked for The Nature Conservancy,” Wistrand said.

“Wildland fire fighting is a small world,” Snodgrass said. “Here you are out in the middle of nowhere and you have three people – me, Hunter and Paul Hanneman – all associated with one little Episcopal church.”

When the Livermore Ranch Complex fire was finally out, it left 13,665 acres burned in and around the Davis Mountains Preserve and another 10,576 acres charred around nearby Spring Mountain. No structure was lost or damaged at the Davis Mountains Resort.

Although fire is “mostly a good thing” for the environment, Snodgrass said the preserve “lost quite a few ponderosa pines we’d rather not have lost.” But the land’s generational recovery will present huge opportunities for researchers to study its rebound, he said.

The son of lifelong Episcopalians, Snodgrass grew up in Brownfield, Texas, attended Texas Tech University, majored in wildlife management and has been at the Conservancy for some 15 years. Johnson City doesn’t have an Episcopal Church, so he, his wife Aylin, two children, mother and brother drive 15 miles south to church in Blanco’s St. Michael.

Wistrand, also a lifelong Episcopalian, grew up in Colorado City in the rolling grass and scrub brush of West Texas where there wasn’t a forest and barely a tree in sight.

How did he end up fighting forest fires?

“When I was in ninth grade, they gave us an aptitude test. Mine showed that I had an aptitude for either a forester, game warden or dentist,” he said. “I knew I didn’t want to spend my career looking down somebody’s throat. So I went into forestry.”

After graduating from Stephen F. Austin State University in the Piney Woods of East Texas, he went to work for the U.S. Forest Service. His first assignment was spraying Southern pine beetles with insecticide. “I’d come home drenched in insecticide,” he said. “I’m lucky I don’t have cancer.”

His next job was hauling trash and cleaning restrooms. “That was a step up from spraying pine beetles,” he said.

The year he got out of college, he went on his first fire in the Santa Fe National Forest, doing the grueling work of cutting fire lines by hand. “When you’re 22, you don’t even think about how hard it is,” he said.

As he advanced in his career, he had a variety of forest service assignments that took him from Texas to Florida to New Mexico before ending up in Flagstaff, Arizona, where his entire job was centered on fire fighting.

After a 29-year career, he retired in 2001 and moved with his wife Virginia to Spring Branch south of Blanco to be near family. His daughter Laura has taught Sunday school at St. Michael for two years and Virginia serves on the altar guild and as an acolyte. The Wistrands bring a passel of grandkids to church with them.

In addition to responding to calls from the Texas Forest Service, Wistrand teaches fire training courses across the nation. He finds life as a semi-retired fire fighter enjoyable.

“There’s no conference calls, no budget meetings, no staff meetings. No meetings of any kind,” he said with a smile.

Despite the rigorous work, fighting fires “is a lot of fun actually,” Snodgrass said. “Most everybody who does it enjoys it. It’s hard work. It’s exciting. It’s a real sense of accomplishment. It’s a finished product, if you will.”

Although devote Episcopalians, neither has much time to think about spiritual matters while on a fire. “There’s no opportunity for church or prayer,” Snodgrass said. “Usually it’s a two-week detail, all day, every day. It’s all about fire.”

In the quietness of an evening, though, Wistrand does take a moment or two to ponder the immensity of nature around him. “I make the connection with God by sitting on a mountain,” he said. “This may sound odd, but sitting on a peak at night time there is nothing prettier than watching the sparkle of a wildfire burning on a hillside with the stars above.”

“Fire is a natural force like tornadoes, hurricanes and volcanos,” he said. “I don’t think the good Lord put these forces here to harm us. I look at fire as a beneficial thing, not a destructive force.”

When he looks at the power of a fire burning through the lands, “that kind of scenery really puts things in perspective about how little influence we have as a single person and who’s really running things here.”

In his reflections, Snodgrass thinks about environmental stewardship. “I love the outdoors. The church makes me think about that. It’s a way to fulfill both my personal and church missions,” he said.

— Mike Patterson is a freelance writer and member of St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church in Blanco. He is a regular contributor to The Church News, a publication of the Diocese of West Texas.

Social Menu