‘Day of Action’ marks 60 days of Occupy Wall StreetInterfaith leaders march over the bridgePosted Nov 18, 2011 |

|

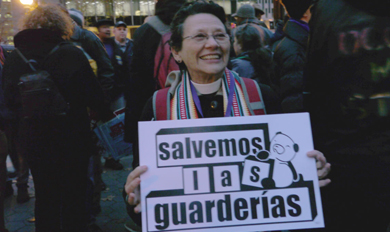

The Rev. Maria Isabel Santiviago, an Episcopal priest in the Diocese of New York and vicar of St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf, joined Nov. 17 with members of Occupy Faith NYC, an interfaith coalition formed in the wake of the Occupy Wall Street movement, at Foley Square. ENS photo/Lynette Wilson

[Episcopal News Service] Thousands of Occupy Wall Street protesters and supporters, including an interfaith contingent, converged on lower Manhattan Nov. 17 for a Day of Action, marking the two-month anniversary of the birth of the worldwide nonviolent protest movement against economic inequality.

Before Occupy, “people were, we were, like zombies … this is a wake up,” said the Rev. Maria Isabel Santiviago, an Episcopal priest in the Diocese of New York and vicar of St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf, in an interview with ENS at Foley Square.

The movement reminds people that they have control of their lives and that they don’t have to “accept things” as they are; it’s leading to a new state of consciousness, she said.

Santiviago joined the protest just before 5 p.m. when interfaith leaders representing Occupy Faith NYC, an interfaith coalition formed in the wake of the OWS movement, met at Foley Square, just north of New York City Hall and the Brooklyn Bridge, in advance of a planned march across the iconic bridge. Many other protesters and supporters gathered alongside City Hill, opposite the pedestrian entrance to the bridge, where a sign flashed two screens yellow on black, first “PEDS ON ROADWAY,” then “SUBJECT TO ARREST.”

But the Day of Action began much earlier, around 7 a.m. when crowds of people and media of every description gathered for instructions and direction at Zuccotti Park — site of the original OWS encampment — and in front of a giant red cube with the hole in the center immediately across Broadway Avenue in front of Brown Brothers Harriman, a privately held financial-services firm with west views into the park.

Protesters intended to march on Wall Street and occupy the space in front of the New York Stock Exchange in advance of the 9:30 a.m. opening bell, which marks the start of the day’s trading session. Instead, New York Police Department officers stopped them at six intersections, each at least a block away from the NYSE, which stands at the corner of Wall and Broad Streets, an area permanently closed to traffic and popular with tourists.

Protesters sitting in the intersection of William and Pine Streets clashed with police, who made arrests. But two blocks south at the intersection of William and Exchange Streets, protesters sat in a circle and shared their stories of involvement with Occupy as police officers watched.

A New Jersey retiree stood in the center of the circle and addressed the NYPD officers directly, saying, “We represent you. You are part of the 99 percent. When you take off your uniforms, join us, join us, join us.”

Zuccotti Park served as the permanent encampment for OWS until an early-morning Nov. 15 eviction of protesters ordered by New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Following the eviction, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in West Harlem was one of five churches to open its doors to “dislocated occupiers,” but as of mid-afternoon on Nov. 17, no one had taken St. Mary’s up on the offer, said Earl Kooperkamp, St. Mary’s rector and a member of Occupy Faith NYC.

Kooperkamp has been involved with Occupy from the beginning. On Sept. 16, the day before the Occupy Wall Street was born, the newly formed “Protest Chaplains” from Boston traveled to New York, spending the night at his church before joining the movement’s launch the next day. Kooperkamp also has visited Occupy encampments in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia.

“I think the OWS movement has captured the imagination of a lot of different people literally around the world,” he said, and then provided an example.

The Rev. Michael Lapsley, a South African Anglican priest and longtime social-justice activist, during a Nov. 10 meeting of Occupy Faith NYC shared the story of a poor South Africa township motivated by OWS.

The township isn’t hooked up to a sanitary sewers system, so its residents use buckets because they don’t have toilets. Inspired by the occupiers, the residents hauled their buckets to a local government office and left them there, vowing to do so daily until the government agrees build a sewer system that will protect their children’s health.

“The world is learning from Occupy Wall Street, and Occupy Wall Street has to learn from the world,” said Kooperkamp.

Outside New York, OWS Day of Action events took place in the United States in Los Angles, San Francisco and Portland, Oregon, and worldwide in places like Greece.

Morning video of events in New York Nov. 17 ran side-by-side with images of marchers in Greece. The OWS website listed plans for university student strikes in Spain, Belgium and Germany and “spontaneous solidarity actions in Tokyo.”

Back in New York, where at 3 p.m. Day of Action protesters staged an attempted occupation of the metropolitan transit system, seminarians wearing cassocks and armed with anointing oil from General Theological Seminary joined protesters at a subway station on the “C” line at Eighth Avenue and 23rd Street. They included Ben Wallis of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, who is following the OWS movement for an individualized study course on pastoral care for marginalized people.

In an ENS interview earlier in the day, Wallis said, “Regardless of what people think [of OWS], it’s an honest and real expression of what people are feeling right now.”

Mary Jetts, GTS’s social justice coordinator, said most students support the movement as an expression of free speech and from the perspective of the church’s stance on poverty, but others don’t understand it.

The Rev. P. Joshua Griffin, a priest associate at St. David of Wales Episcopal Church, has been active with Occupy Portland, where on Nov. 17 police and protesters clashed at a downtown bank. One of the movement’s tactics, which resonates well with the climate-justice movement, is the “occupation” of banks, Griffin said in a telephone interview with ENS earlier in the day.

An advocate of the climate-justice movement — on offshoot of the environmental movement that specifically attempts to alleviate climate change’s unequal burden on poor and indigenous communities — and a supporter of OWS, Griffin described the movement in liturgical terms.

“This is not a protest movement, it is public liturgy of the finest sort. This movement is powerful because it is showing us a way forward — the general assemblies may be the only truly democratic spaces in this country,” he said, referring to the movement’s regular meetings where members make decisions via consensus as part of the OWS “horizontal” leadership structure.

“You cannot have democracy and inequality; it’s one or the other. You cannot pray for peace and not struggle for justice — right now that struggle is in the streets, the bank lobbies, the public squares,” he said.

Griffin also said that the movement, while standing with homeowners facing foreclosure in places like Minnesota and working with them and their lenders to renegotiate mortgages, was doing more to help people than U.S. policy makers.

“Occupy is changing the public discourse and refocusing our attentions where they should be,” he said, adding that the church must start to refocus itself.

“I think our church needs to have a very serious conversation; it’s completely embedded and dependant on the exploitative economy, based on the extraction and consumption of resources. We need to figure out how to free ourselves from those dependencies.”

The Diocese of Long Island and the Episcopal Church’s Executive Council have passed resolutions supporting the movement.

In San Francisco, the Rev. Vicki Gray, a deacon at Christ the Lord Episcopal Church, Pinole, California, and a member of the steering committee of San Francisco’s Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice (CLUE), said the committee formed San Francisco Interfaith Allies of Occupy on Nov. 14. It adopted a theological statement, “A call to Shalom,” written by Gray.

The interfaith allies, she said, planned to gather at Justin Herman Plaza, home to Occupy San Francisco, to issue statements of support for the movement and participate in nonviolent training in anticipation of a police crackdown. As of Nov. 18, the city’s main encampment had not been raided.

Police have ousted campers in other sites, however, ranging from Zuccotti Park to Dallas, Portland and Oakland, California, and in Canada in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and London, Ontario. In England, the City of London Corporation on Nov. 17 proceeded with eviction notices for protestors camped on the land it owns surrounding the precincts of St. Paul’s Cathedral, giving them until 6 p.m. (1 p.m. EDT) to clear the “public highways” or face legal action. The protestors have said they have no intention of moving from the site.

As of the morning of Nov. 18, guard rails surrounded Zuccotti Park, limiting but not forbidding public access, and more than a dozen private security guards wearing bright green safety vests lined the perimeter. A few protesters stood on the sidewalk holding signs, and one said he expected the park to officially reopen later in the day. A court order bans the use of sleeping bags, tents or other camping equipment in the park.

Boston’s mayor has said he has no plans to ask campers to move, and a court Nov. 16 upheld their right to remain in Dewey Square. Protestors marched through the city on Nov. 17. Protest Chaplains are maintaining a faith and spirituality tent for occupiers at the Boston encampment.

The Rev. Jim Friedrich, an Episcopal priest in the Diocese of Olympia who attended seminary in the 1960s when the “campus ministers were on the frontline of things,” said he had been wondering about “when are people going to speak up about all the terrible things we are allowing to happen?”

Friedrich and a fellow priest signed up for the rota at Occupy Seattle’s sacred space. Following a service, a dozen people gathered in the tent under candlelight.

“It was just a real wonderful engagement, and we all felt a connection … it’s a diverse group of people that collect in these Occupy sites.

“But also there was just something about that tent and that moment in the candlelight … we don’t have those kinds of conversations. It’s a village culture, a pre-modern [civilization] … everyone is just kinda there and available,” he said. “For those of us who live in the anonymous urban culture, its refreshing to be in a camp just hanging out, let down barriers and much more naturally together.”

One of the wonderful things about the movement, Friedrich said, is the uncertainty. No one really knows where it’s going, and so far it’s resisted being co-opted by even “good causes,” he said.

One thing is for certain, though, he added, “the poor haven’t been talked about in such a way since the 1960s and Bobby Kennedy.”

— Lynette Wilson is an ENS editor/reporter. ENS correspondent Sharon Sheridan contributed to this report.

Social Menu