Historic American-Scottish roots celebrated through Presiding Bishop’s visit to AberdeenPosted Nov 6, 2017 |

|

The ornate crests of the American states on the ceiling in the nave of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Cathedral in Aberdeen, Scotland, symbolize the deep connection between the Scottish and U.S.-based Episcopal churches. Photo: Matthew Davies/Episcopal News Service

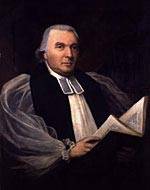

[Episcopal News Service – Aberdeen, Scotland] Ornate crests of the American states decorate the ceiling of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Cathedral in Aberdeen, Scotland. It’s a reminder of the critical role the U.S.-based Episcopal Church played in laying the groundwork for global Anglicanism when it sent Samuel Seabury to the British Isles in 1784 to be consecrated as its first bishop.

Faced with an unworkable condition from the Church of England calling for Seabury to swear allegiance to the crown, he traveled to Aberdeen where three Scottish bishops agreed to consecrate him in return for promoting the Scottish Prayer Book liturgy back on American soil.

More than 230 years later, Presiding Bishop Michael Curry arrived in Aberdeen for a four-day visit to Scotland to recognize the importance of that significant moment in history and to celebrate the partnership that has flourished between the two provinces ever since. Curry is accompanied by Executive Assistant Sharon Jones and the Rev. Chuck Robertson, canon for ministry beyond the Episcopal Church, who was installed on Nov. 5 as an honorary canon of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Cathedral in Aberdeen during a Festal Evensong. Curry preached during the service.

“Our bishops today trace their succession to Samuel Seabury … so our roots really are here in Aberdeen, Scotland,” Curry told Episcopal News Service on Nov. 6 before joining a symposium exploring the social history and common interests of the Scottish and U.S.-based Episcopal churches. “Indeed, Scotland is our mother church, so it was good to come home and give thanks to our mother church and to affirm our continued partnership in Jesus Christ.”

Curry’s reference to coming home was mutually acknowledged by his Scottish hosts as he was invited during a post-service reception to cut a cake iced with the words “Welcome Home.” The delegation was then furnished with gifts of Scotch whisky and porridge stirrers, representing perhaps two longstanding staples in the Scottish diet.

The Most Rev. Mark Strange, bishop of Moray, Ross and Caithness and primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church, said that the Scottish Episcopal Church “is proud of its role in the coming into being of what is now the worldwide Anglican Communion, and I am delighted to welcome the presiding bishop in his first visit to Scotland when we can share our past, present and future bonds of communion and concern for the people we serve in our respective provinces.”

Strange, who as a young boy sang in the choir at St. Andrew’s Cathedral, told ENS that for as long as he can remember “there has been a close link with America. Last night, I had the real pleasure of installing Chuck Robertson as a canon. I’ve watched canons from America being installed my whole life. And there’s a sense in which when I am in North America, this is home.

“For the Scottish Episcopal Church, just having the knowledge that somehow we are connected … means that we are more outward-looking than inward-looking.”

The historic bond that St. Andrew’s Cathedral shares with the Episcopal Church includes an invitation for the presiding bishop to nominate someone to be installed as an honorary canon.

“Their affection for our church and our affection for the Scottish Episcopal Church is longstanding and deep,” said Curry. “And now we must take that affection into concrete work that helps to change the world into something akin to God’s dream for it, and so Canon Robertson being made an honorary canon was a symbolic way of incarnating that in a human person.”

Meanwhile, the Very Rev. Isaac Poobalan, cathedral provost, hopes the visit will raise further awareness of the role that the cathedral plays in the community of Aberdeen’s city center and beyond.

When Seabury reached London back in 1784, bishops in the Church of England thwarted his mission to the episcopate. The English church, standing firm in its post-Reformation ideals, insisted he swear an oath of allegiance to the king. Such an oath would have contravened America’s Declaration of Independence, and with the colonies having won the war of independence one year earlier, Seabury was wise to decline.

Instead, he took to the road, traveling 400 miles north to Scotland. There, the Episcopal Church in Aberdeen and Orkney willingly assisted with his consecration, and with a more workable condition – that he promote the Scottish Prayer Book upon returning home.

St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Aberdeen, Scotland, holds a special place in the legacies of both the U.S.-based Episcopal Church and the Scottish Episcopal Church. Photo: Matthew Davies/Episcopal News Service

This milestone is often heralded as the main catalyst, if not the onset, of what eventually would become known as the Anglican Communion. The relationship between the U.S.-based Episcopal Church and the Scottish Episcopal Church has deepened and flourished over the more than two centuries since that momentous occasion, including through a close companion relationship between the Diocese of Connecticut and the Diocese of Aberdeen and Orkney.

To this day, despite several prayer book revisions, the Rite I Eucharistic Prayer in the Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer is strikingly similar to the same liturgy found in the Scottish Prayer Book.

But Curry also noted that “the red, white and blue – and that particular shade of blue in the Episcopal Church flag – hail from Scotland. And indeed, our very name, the Episcopal Church, comes from the Scottish Episcopal Church. So, in those symbolic yet significant ways, there are ties that bind us. But I have a feeling there’s a deeper DNA. There’s kind of an American spirit that has a lot to do, I think, with the spirit of Scotland, and that sense of freedom and independence. That’s pretty American, and I have a feeling we get that from Scotland.”

Seabury was born in Groton, Connecticut, and graduated from Yale College in 1748. He read theology under his father and then studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, 1752-1753. Seabury was ordained deacon on Dec. 21, 1753, and priest on Dec. 23, 1753, in England. He was a missionary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1754-1757, and rector at Jamaica, New York, 1757-1766.

From 1766 to 1776 he served as rector of St. Peter’s Church, Westchester, New York, and from 1776 to 1783 he was in private medical practice and chaplain to British troops at Staten Island and New York. He wrote forceful pamphlets in defense of loyalty to the British Crown. On Mar. 25, 1783, he was elected bishop of Connecticut and was consecrated at Aberdeen, Scotland, Nov. 14, 1784, by three nonjuring bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church.

He also served as bishop of Rhode Island from 1790 to1796 and as presiding bishop from 1789 to 1792. He was a high churchman in the tradition of the nonjurors and the Caroline Divines. A valid episcopacy and the threefold orders of clergy were central concerns for him. He died in 1796 in New London, Connecticut. Seabury and the passing of the episcopate to the Episcopal Church are commemorated on Nov. 14 in the Episcopal calendar of the church year.

In the decades following Seabury’s death, the communion grew geographically and numerically, largely through the missionary movement, and many more-complex cultural and contextual issues came into play. Other than in its prayer book, the Anglican Communion staved off making any foundational declaration until the 1888 Lambeth Conference endorsed the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, originally adopted by the Episcopal Church’s House of Bishops in 1886.

The Quadrilateral named four principles of Anglicanism: the Holy Scriptures, as containing all things necessary to salvation; the creeds – specifically the Apostles’ and Nicene creeds – as the sufficient statement of Christian faith; the sacraments of baptism and Holy Communion; and the historic episcopate, locally adapted. (A U.S. Episcopal priest, William Reed Huntington, is credited with proposing the four elements in an 1870 essay.)

Today, the communion encompasses 39 autonomous provinces with some 80 million Anglicans in 165 countries worldwide. But it’s anyone’s guess what the landscape of the Anglican Communion would look like in 2017 had Seabury not ventured to Scotland in search of his episcopal consecration.

But the path of the Anglican Communion has been far from smooth at times, with the spotlight over recent decades highlighting the differences over biblical interpretation concerning women’s ordination and human sexuality issues. To date, the Scottish and U.S.-based churches are the only provinces to have voted to remove from their canons the definition that marriage is between a man and a woman, thus enabling gay and lesbian Christians to be married in church.

“The Anglican Communion has its difficulties, has its concerns, and we need to find ways of working together so that when we really get down to issues, we know that the issues we are talking about are the ones that concern us for the world,” said Strange. “For a small church like ours to be able to be a part of a larger institution is always important. … I am looking forward to maintaining what is clearly already a loving relationship and to finding ways to build on that.”

Curry agreed, saying, “We are not isolated, disparate individuals. We are part of a greater whole. Dr. Martin Luther King said we are tied in networks of mutuality in a single garment of destiny. The truth is we are interconnected, we are interrelated, and the more we use our interconnectedness and our relationships for the good, the better off the whole world is.”

– Matthew Davies is advertising and web manager for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu